Potential for Big El Nino this Winter

The strengthening El Niño in the Pacific Ocean has the potential to become one of the most powerful on record, as warming ocean waters surge toward the Americas, setting up a pattern that could bring once-in-a-generation storms this winter to drought-parched California.

The National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center said Thursday that all computer models are predicting a strong El Niño to peak in the late fall or early winter. A host of observations have led scientists to conclude that “collectively, these atmospheric and oceanic features reflect a significant and strengthening El Niño.”

“This definitely has the potential of being the Godzilla El Niño,” said Bill Patzert, a climatologist with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge.

El Nino: 1997 vs. 2015

At the moment, this year’s El Niño is stronger than it was at this time of year in 1997. Areas in red and white represent the highest sea-surface heights above the average, which are a reflection of how warm sea-surface temperatures are above the average. (Source: NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory climatologist Bill Patzert)

Patzert said El Niño’s signal in the ocean “right now is stronger than it was in 1997,” the summer in which the most powerful El Niño on record developed.

“Everything now is going to the right way for El Niño,” Patzert said. “If this lives up to its potential, this thing can bring a lot of floods, mudslides and mayhem.”

“This could be among the strongest El Niños in the historical record dating back to 1950,” said Mike Halpert, deputy director of the Climate Prediction Center.

After the summer 1997 El Niño muscled up, the following winter gave Southern California double its annual rainfall and dumped double the snowpack in the Sierra Nevada, an essential source of precipitation for the state’s water supply, Patzert said.

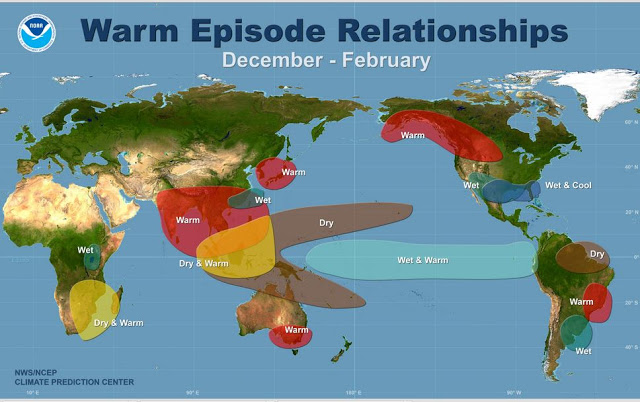

A strong El Niño can shift a subtropical jet stream that normally pours rain over the jungles of southern Mexico and Central America toward California and the southern United States.

But so much rain all at once has proved devastating to California in the past. In early 1998, storms brought widespread flooding and mudslides, causing 17 deaths and more than half a billion dollars in damage in California. Downtown L.A. got nearly a year’s worth of rain in February 1998.

During the second largest El Niño on record, in the winter of 1982-83, damage was particularly severe along the coast, especially when powerful storms arrived as high tide surged onto the coast. “Particularly at the end of January 1983, we had some very strong storm wave effects along the coast, and a lot of the vulnerable structures were lost that winter,” said Dan Cayan, climate researcher with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego and the U.S. Geological Survey.

“Many locations along the California coast recorded their highest sea levels during that winter,” he said.

The effects of this muscular El Niño – nicknamed “Bruce Lee” by one blogger for the National Weather Service – are already being felt worldwide. While a strong El Niño can bring heavy winter rains to California and the southern United States, it can also bring dry weather elsewhere in the world.

Already, El Niño is being blamed for drought conditions in parts of the Philippines, Indonesia and Australia, as occurred in 1997-98.

Drought is also persistent in Central America. Water levels are now so low in the waterways that make up the Panama Canal that officials recently announced limits on traffic through the passageway that links the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

El Niño also influenced the heavy rainstorms that effectively ended drought conditions in Colorado, Texas and Oklahoma, and has brought floods and mudslides to Chile.

There are a couple of reasons why scientists say El Niño is gaining strength.

First, ocean temperatures west of Peru are continuing to climb, reaching their highest level so far this year. The temperatures in a benchmark location in that area of the Pacific Ocean were 3.4 degrees Fahrenheit above the average as of Aug. 5. That’s slightly higher than it was on Aug. 6, 1997, when it was 3.2 degrees Fahrenheit above normal.

The mass of warm water in the Pacific Ocean is also bigger and deeper than it was at this point in 1997, Patzert said.

Second, the so-called trade winds that normally keep the ocean waters west of Peru cool — by pushing warm water farther west toward Indonesia — are weakening.

That’s allowing warm water to flow eastward toward the Americas, giving El Niño more strength.

For this year’s El Niño to truly rival its 1997 counterpart, there still needs to be “a major collapse in trade winds from August to November as we saw in 1997,” Patzert said.

“We’re waiting for the big trade wind collapse,” Patzert said. “If it does, it could be stronger than 1997.”

There is a small chance such a collapse may not happen.

“There’s always a possibility these trade winds could surprise us and come back,” Patzert said.

Overall, the Climate Prediction Center forecast a greater-than-90% chance that El Niño will continue through this winter in the Northern Hemisphere, and about an 85% chance it will last into the early spring.

In California, officials have cautioned the public against imagining that El Niño will suddenly end the state’s chronic water challenges.

In fact, it would take an astonishing 2.5 to three times the average annual precipitation to make up for the rain and snow lost in the central Sierra mountain range over the last four years of drought, said Kevin Werner, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s expert on climate in the western United States.

That amount far exceeds what happened in 1983, the wettest year on record for that region, when the area got 1.9 times the average annual precipitation, Werner said.

“A single El Niño year is very unlikely to erase four years of drought,” Werner said.

“The drought is not ending any time soon,” Halpert added.

California has been dry for much of the last 15 years. Even if California gets a wet winter this year, it could be followed by another severe multiyear drought.

Another problem is that the Pacific Ocean west of California is substantially warmer than it was in 1997. That could mean that though El Niño-enhanced precipitation fell as snow in early 1998, storms hitting the north could cause warm rain to fall this winter. Such a situation would not be good news “for long-term water storage in the snowpack,” said Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at Stanford University.

Drought officials prefer snow in the mountains in the winter because it slowly melts during the spring and summer and can trickle at a gentle speed into the state’s largest reservoirs in Northern California. Too much rain all at once in the mountains in the winter can force officials to flush excess water to the ocean to keep dams from overflowing.

Swain said it’s important to keep in mind that all El Niño events are different, and just because the current El Niño has the potential to be the strongest on record “doesn’t necessarily mean that the effects in California will be the same.”

“A strong El Niño is very likely at this point, namely because we’ve essentially reached the threshold already, but a wet winter is never a guarantee in California,” Swain said in an email.

“I think a good way to think about it is this: There is essentially no other piece of information that is more useful in predicting California winter precipitation several months in advance than the existence of a strong El Niño event,” Swain said. “But it’s still just one piece of the puzzle. So while the likelihood of a wet winter is increasing, we still can’t rule out other outcomes.”